Letter from the curator #2: the All-Female Traditional Korean Theatre

Dear readers,

“Japan has surrendered!” his voice rang. “Korea is independent!” [...] Like a dam breaking at the last raindrop, people poured out onto the streets with breathtaking speed. [...] [T]ens of thousands of people, embracing, singing, crying, and shouting manseh.

Manseh is a Korean word meaning ‘Hurrah or ‘Long live’.

Juhea Kim (2021:350). Beasts of a Little Land.

It was August 15, 1945, after 35 years of Japanese colonial rule that Korea was liberated. The day is now celebrated in South Korea as Gwangbokjeol, meaning the day the light returned. However, liberation did not bring instant freedom. The peninsula was soon caught in a tug-of-war between US and Soviet occupation, then swept into the Korean War. The colonial systems, rigid class divisions, and Confucian patriarchy remained deeply rooted, and the marginalized were pushed further to the edges.

***

In this climate, there was one rare space where norms could be bent, and women’s voices could speak boldly: Yeoseong Gukgeuk, ‘the All-Female Traditional Korean Theatre’. In Yeoseong Gukgeuk, every role was played by women. Its roots go back to the Gisaeng, ‘female artists’ in the Joseon era who were highly skilled in music, dance, and poetry, but socially ranked among the lowest. Under the influence of Japanese imperialism, the class system was officially abolished in 1894, but discrimination against women, especially those from marginalized backgrounds, continued. Many Gisaeng and women performers were pushed to the very margins, stripped of institutional protection.

Archive Still from the Girl Princes (dir. Hye-jung Kim), screened at the 14th Seoul International Women’s Film Festival (2012), featuring a scene from the play ‘The secret of princess palace’

***

Following Korea’s liberation in 1945, former Gisaeng and female musicians sought new ground for both livelihood and artistry. In 1948, they formed the Women’s Korean Music Association. But the male-dominated traditional music world refused to grant them space, so they created their own space: a form of Changgeuk, traditional opera, performed entirely by women. Their first production, Okjunghwa (‘Blossoms in Prison’), marked the birth of Yeoseong Gukgeuk. It was a stage where women from the lowest social classes could reclaim their voice and shine through the patriarchal, colonial order that still lingered in the arts.

Even during the Korean War, the performances continued. In the post-war years, Yeoseong Gukgeuk reached the height of its popularity. Theatre companies adapted Korean folktales which had been erased during colonial rule into sweeping romance and heroic tales. The male role in the ‘beautiful boy’ played by women became beloved icons, as the characters are courageous warriors with devotion to their lovers. On these stages, women reshaped masculinity from their own perspectives. Tickets sold out daily and fan culture was intense: one fan staged an imaginary wedding photoshoot with star actress Geum-Aeng Jo. The theatre became a safe outlet for long-suppressed desires, channeled into passionate fandom.

Still from the Girl Princes (dir. Hye-jung Kim) screened at the 14th Seoul International Women’s Film Festival (2012).

By the late 1950s, however, Yeoseong Gukgeuk’s popularity faded out. The state heavily promoted the film industry, alongside the spread of the television. Above all, prejudice against a women-led art persisted. For many actresses, this decline meant losing not only a career but also their economic and social independence. Yeoseong Gukgeuk was never just about entertainment. In the turbulent post-liberation years, it was a decolonial space, a site where marginalized women could claim their bodies, voices and desires.

***

siren eun young jung, A Performing by Flash, Afterimage, Velocity, and Noise, 2019, Audiovisual installation, multi-channel video, stereo and 5.1 surround sound, dimension variable. Image Courtesy of the Artist and Korean Pavilion, La Biennale Di Venezia 2019, Photo by Chulki Hong.

Since 2008, contemporary artist siren eun young jung* has been researching and reimagining this legacy through video, performance, and archival works. In her early projects, she focused on the covert power relationship of the act of ‘becoming man’ on stages of Yeoseong Gukgeuk, and the queer moments in the relationships between actors and their fans that disrupted mainstream gender norms. jung’s (2009) work, The Masquerading Moments, captures first-generation actresses from the 1950s applying their male-role makeup once again. As the camera lingers, we see the quiet transformation: from individual to character, from woman to man, from the present moment back into the past.

*The artist’s english name, siren eun young jung, is intentionally written in lowercase to make it obscure to discern aspects such as nationality, gender, racial, or class background. See here for Ute Meta Bauer’s work “Deferred Histories - Speaking Uncomfortable Truths: On the Work of siren eun young jung Queering Korean Cultural History’.

siren eun young jung, The Masquerading Moments, 2009, Single channel video, 08 min. 16 sec. Image courtesy of the Artist

Through her work, jung explores the cracks Yeoseong Gukgeuk created in the social order, and how those fractures can still open space for resistance today. The voices that history tried to silence are called back, reframed in new language and vision. A century after the colonial period began, the memory of Yeoseong Gukgeuk still asks us: can this stage, now fading from memory, be reimagined as a space for thinking about gender, power, and the traces of colonialism?

***

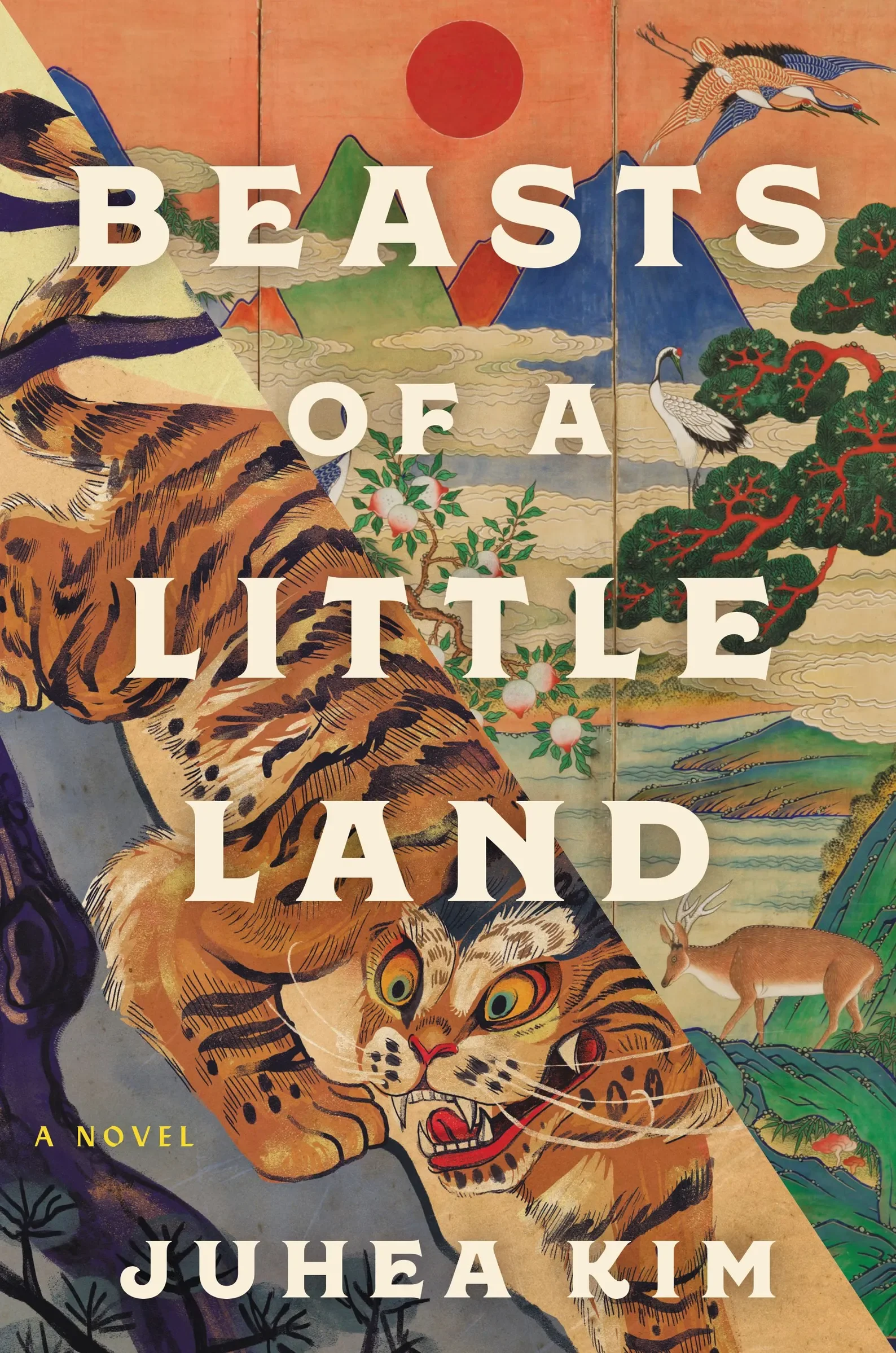

The Year 2025 marks the 80th anniversary of many Asian nation’s liberation from their colonial rule. For those who want to explore the history of Korea’s liberation through fiction, I highly recommend Juhea Kim’s beautiful novel Beasts of a Little Land, which I quoted at the beginning. Awarded the 2024 Tolstoy Prize for Foreign Literature, and named a finalist for the 2022 Dayton Literary Peace Prize, the novel tells the intertwined stories of ordinary people struggling to reclaim their light in extraordinary times.

Cover of Beasts of a Little Land by Juhea Kim (published by Ecco)

***

Warmly,

Jeongwon Seo

Curator at the Busan Museum of Art

Jeongwon is interested in examining how capitalism shapes perception through propaganda, drawing on her studies in Business and Art Mediation.

Author: Jeongwon

Translator: Hyunjung

Editor: Jiye

Image: siren eun young jung