Letter from the curator #3: A Story of Oseonbo: Sounds Lost in Translation

Dear readers,

When I think back to the first time I learned music in school, I remember the blackboard in the music room covered with a five-line staff. I practiced drawing travel and bass clefs over and over again, filling the pages with notes, while we sang the Korean version of “Do-Re-Mi” song to learn the scale.

Many of us probably share this similar memory. Western music notation, as we know it today, was invented around the year 1000 by the italian musician Guido d’Arezzo and evolved over the centuries into modern five-line staff. For most of us, Solfège Syllables and staff notation have become the ‘universal’ language of music. But of course, they are not the only way to read and write sound. When did we start using this system widely? And what happened to the musical knowledge that existed before it?

Hansongjeong, a song from the Goryeo period (918-1392). Copied in Joengganbo notation, a copyist unknown (presumed early 20th century). Courtesy of Collection of National Hangeul Museum

***

In 1915, the missionary magazine, The Korea Mission field, published an article titled “Korea’s Musical Progress.” It dismissed Korean vocal music as “all sung on the same pitch” and “not good music.” This was in fact a misunderstanding; Korean music did not use semitones, a concept essential to Western scale. Korean and Western music were built on different systems.

Long before Western notation arrived, Korea already had its own method for recording and transmitting sound. Developed around 1440 by King Sejong, Jeongganbo used a grid of square boxes to represent duration and pitch. It was a knowledge system suited to the structure of Korean music. However, by the late 19th century, European colonial powers reached Asia under the banner of “Christian mission". Through schools and churches, Western music and notation spread across the region. In Korea, western music soon claimed the status of ‘modern’ and ‘universal’, pushing indigenous notation like Jeongganbo to the margin, treated as outdated, non-standard, and eventually erased from education and cultural institutions.

***

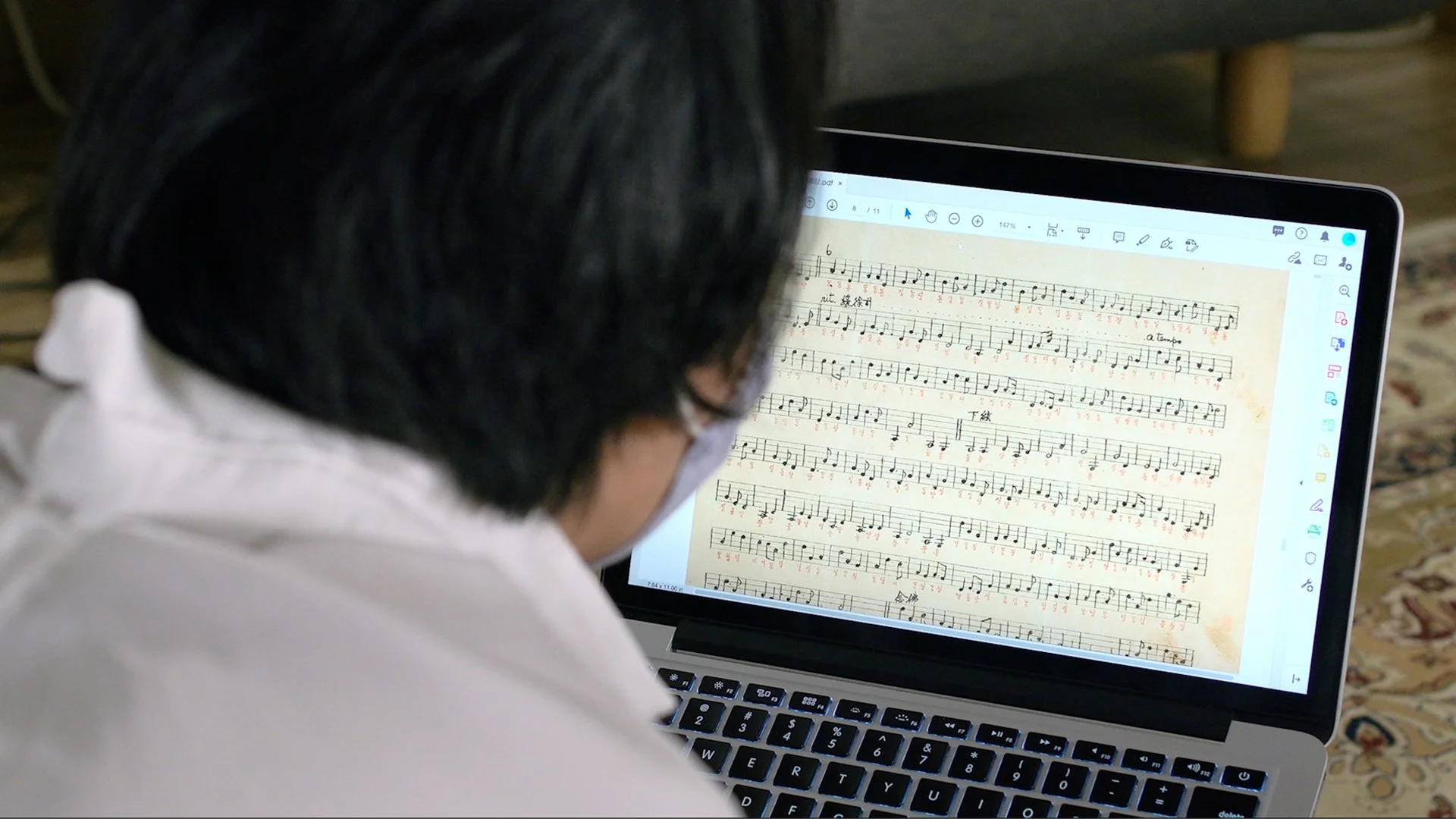

The contemporary artist Young-Eun Kim’s (South Korea) work A story of Oseonbo: sound lost in Translation (2022)looks closely at this moment of historical entanglement. As a point of departure, the work explores how the introduction of Western music during colonial expansion reshaped not only Korea’s musical system but its way of listening and knowing. In 1914, In-Sik Kim, an early adopter of Western music in Korea, transcribed the score of Yanggeum (Korean traditional musical instrument similar to dulcimer) for the piece Yeongsan Hoesang into Western staff notation for the first time. This became Joseon Guak Yeongsanhoesang, an rare artifact of a cultural translation with lasting effects.

A Story of Oseonbo: Sounds Lost in Translation, 2022, Single-channel video, stereo sound, 47 min. 8 sec. Courtesy of the artist.

The work begins with three questions:

Why did In-Sik Kim choose to transcribe Yeongsanhoesang?;

Why was the Yanggeum chosen, not another instrument?;

What sounds were lost in translation from Jeongganbo to staff notation?

It is the last question that the artist follows most closely. The shift from Jeongganbo to staff notation wasn’t a neutral technical change; It was part of broader colonial modernity that imposed a single framework on multiple ways of knowing and erased local voices in the process. This mirrors the logic of our contemporary world, where “efficiency” often justifies standardization and silencing.

Young-Eun Kim asks: who decides what counts as standards? Whose voices were adopted and whose were erased in the making of this global language of music? She approaches listening not as a neutral act but as a deeply political one, shaped by power, ideology, and colonial history.

A Story of Oseonbo: Sounds Lost in Translation, 2022, Single-channel video, stereo sound, 47 min. 8 sec. Courtesy of the artist. Installation cut of the15th Gwangju Biennale (Han Hee Won Art Museum, Gwangju, 2024). Image courtesy of Gwangju Biennale Foundation. Photo: Studio Possiblezone.

A Story of Osenbo reveals the violence hidden in today’s standardized systems. By carefully retracing the layer of Yeongsanhoesang beneath the imposed Western framework, the work invites us to ask: what disappears when diversity is forced to fit into a single system? This is not just a story about sound. It’s about language, education, and culture today about what has been silenced, and what we can still choose to hear.

***

YoungEun Kim's work examines sound and listening as sociopolitical and historical products and practices. Her recent works explore how sound and listenin are constructed and technically developed within specific historical contexts, and what possibilities listening offers in knowledge production and decolonizatio processes. Her work has been presented at the Gwangju Biennale; M+ Museum, Hong Kong; Museum of Fine Arts Bern, Switzerland; Samsung Museum of Art, Korea; Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery, USA; and many others. She has recieved ACC Future Prize and awarded at the Prix Ars Electronica, the SongEun Art Award and Jecheon International Music and Film Festival. She was an artist-in-residence at Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten in Amsterdam and is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Film and Digital Media at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

***

Warmly,

Jeongwon Seo

Curator at the Busan Museum of Art

Jeongwon is interested in examining how capitalism shapes perception through propaganda, drawing on her studies in Business and Art Mediation.

Author: Jeongwon

Translator: Hyunjung

Editor: Szilvia

Image: YoungEun Kim